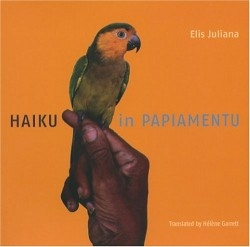

Haiku in Papiamentu Un Mushi di Haiku

Spoken in Aruba, Bonaire, and Curaçao (those islands in the Caribbean popularly known as the Netherlands Antilles), Papiamentu is a Creole language, a combination of Aboriginal, African, Spanish, and Dutch languages. The author, an ethnographer and visual artist and a native of Curaçao, chose to write a series of haiku in this language, with its legacy of colonialism and subsequent freedom, celebrating the island heritage. As with many Creole languages, people ignored Papiamentu, casting it as inferior to the language of the colonial oppressor; however, the tide has changed, and Papiamentu is finally being recognized as a language of great import as it represents and signifies this particular island culture and history.

The translator, also a native of Curaçao, wrote a master’s thesis on the significance of Juliana’s contribution to the revival of Papiamentu in his writing and its effects on the Dutch Antilles. Her translations further that project, introducing readers to the author’s commitment to celebrating the Afro-Caribbean culture and by extension, its language. Juliana chose the haiku to introduce the form to his own culture and to value Papiamentu. Like so many other traditions, the haiku gained prominence in Europe only after academic study, though it was the poetry of the Japanese people, from peasant to royalty; the parallel in projects is clear. The book’s format stresses the importance of the people’s language, with poems printed side by side in English and Papiamentu.

Many of the haiku begin with the traditional Japanese notion of nature, the seasons, and the deep image, encouraging readers to think not only of the image, but the season it invokes and the feeling of that season. Juliana employs the flora and fauna of his homeland to invoke the daily life of the islands: “Upon every leaf / the hand of God has written / the date of demise.” He also interjects humor, commentary on gender roles, critiques of money and greed, and general wisdom.

A number of these poems might read as aphorisms, dressing Juliana as a kind of island Aesop: “A parrot always / can defend himself saying / ‘Someone else said it!’” Others seem like epitaphs: “This is my home now. / The former one I just could / no longer afford.”

The haiku are largely fun and evocative, although occasionally stilted, suggesting that English follows very different rhythms than Papiamentu. Still, as an insight into the ways in which a language and a literature can help to define a culture, these poems provide a way of accessing a little studied society.

Reviewed by

Camille-Yvette Welsch

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.